Where is the Divine? Neuroqueer Talmud is Back!

January 25 · February 1 · February 8 · February 15

Where do we encounter the Divine in the Talmud?

Is the Divine present, absent, hidden, fragmented, relational, emergent?

And what happens when we ask those questions from neurodivergent, disabled, queer, and marginalised bodyminds?

This four-session Neuroqueer Talmud course explores some of the most charged and intimate questions that our rabbinic ancestors ask - not abstract theology, but lived, embodied encounters with the Divine. We’ll study texts that wrestle with presence and absence, prayer and doubt, closeness and distance, certainty and rupture. We’ll sit inside the tensions rather than resolving them too quickly.

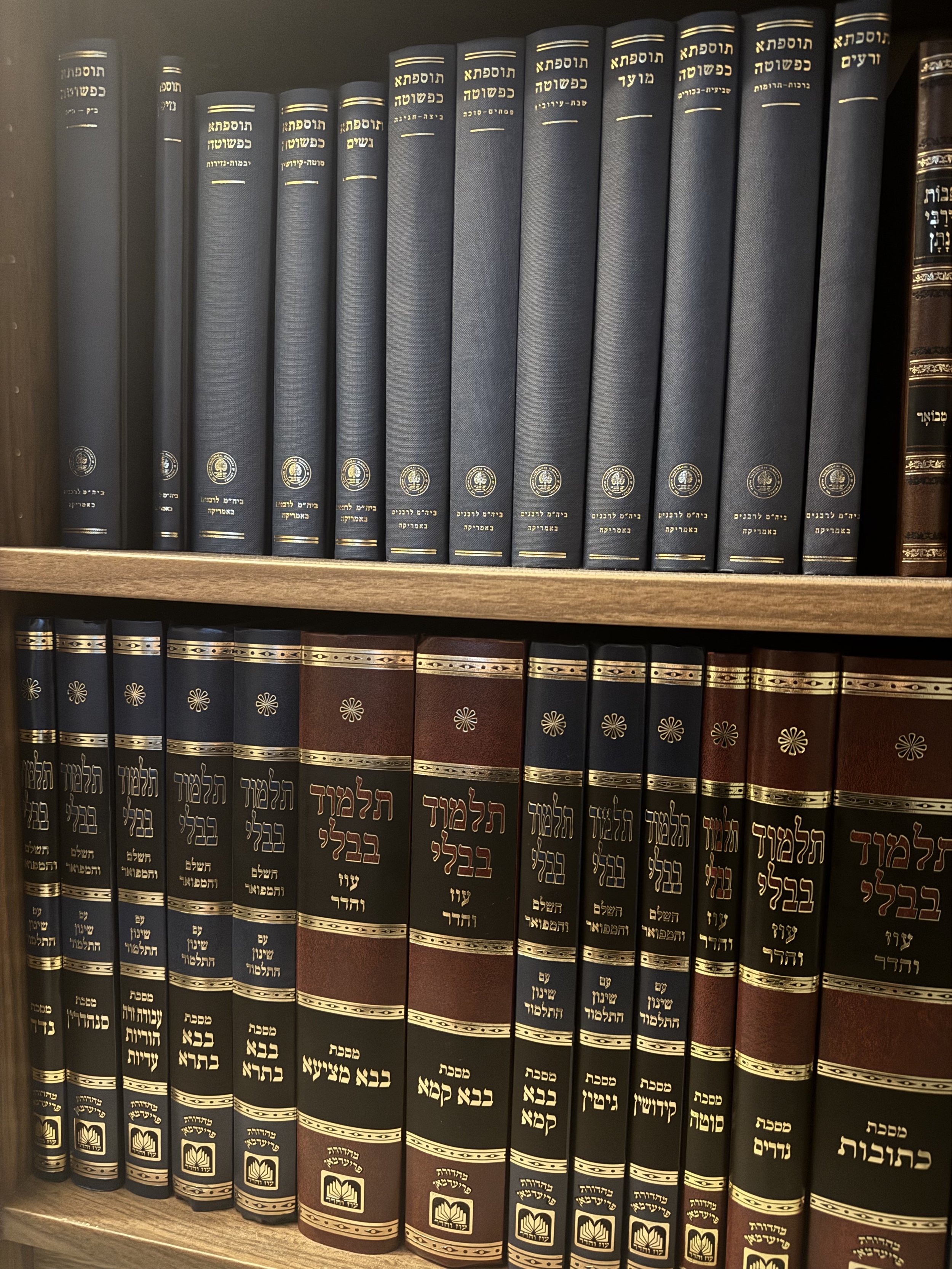

Our primary text will be Masechet Brachot from the Babylonian Talmud, the tractate most explicitly concerned with prayer, blessing, daily rhythms, and the texture of religious life. We’ll read carefully and slowly, paying close attention to how the rabbis talk around the Divine as much as how they talk about the Divine. We’ll also work with Rashi, not as an authority to settle meaning, but as a thinking partner in conversation with the sugya.

How We Learn

This class is taught using the SVARA method. That means a close, rigorous reading of the text in chevruta (paired study), centring questions rather than answers, trusting lived experience as a source of insight, and letting the text argue back. We learn through productive discomfort, not performance.

SVARA-style learning assumes that Torah emerges through encounter - between learners, between perspectives, and between the text and our own lives. Neuroqueer Talmud pushes this further by explicitly centring neurodivergent and disabled ways of thinking, sensing, questioning, and meaning-making. We don’t leave parts of ourselves at the door in order to study. Those parts are the study.

You don’t need to “believe” anything in order to participate. Doubt, ambivalence, anger, longing, and confusion are all welcome here. The rabbis model that kind of relationship to the Divine constantly, and we take them seriously when they do.

Who This Is For

This series is open to people of all learning levels, with one important requirement: participants must have previously taken a class with me, or have learned using the SVARA method elsewhere (at SVARA or in another SVARA-based learning space).

That requirement exists because this is a short, four-week course. We won’t have an extra session to settle in or to introduce the learning tools, chevruta norms, and shared language that this method relies on. We’ll be in the text immediately, and the pacing assumes some familiarity with how this kind of learning works.

This class does continue to develop skills - close reading, question-framing, chevruta practice, and learning to stay with tension in the text. But it assumes those tools have already been introduced elsewhere so we can use our limited time well.

If you’re newer to this style of learning, I’ll be offering an eight-week Neuroqueer Talmud course in the spring that will focus much more explicitly on building and practicing those tools from the ground up, with more time to settle in and experiment. Both courses matter. They’re just designed for different rhythms.

Why Neuroqueer Talmud?

Neuroqueer Talmud treats the rabbinic corpus as something alive, unstable, and deeply human. The rabbis of the ancient world are not offering a neat theology. They are negotiating exhaustion, ritual failure, mystical longing, communal pressure, fear, habit, intimacy, and rupture. They contradict themselves. They preserve minority voices. They refuse closure.

From a neuroqueer perspective, we don’t see this as a flaw. It’s the entire point.

We’ll read the Talmud with attention to how the Divine shows up in moments of breakdown and uncertainty, how prayer functions as regulation, rhythm, and resistance, what it means to speak to, about, or around the Divine, and where absence itself becomes a form of presence.

This is rigorous, relational learning for people who think sideways, feel intensely, ask inconvenient questions, and want Talmud to be more than an intellectual exercise. It’s a space that trusts the text, trusts the learners, and trusts that Torah can hold complexity without collapsing it.